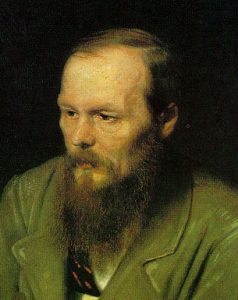

In 1849, Fydor Dostoyevsky was arrested for Inciting against the Russian government because he read an essay by Vissarion Belinsky. Had he known that it would not be on the test, he wouldn’t have bothered reading it, and so the trajectory of one of the greatest existential thinkers of all time would have been changed, not because of what Belinsky said, but because Dostoyevsky’s wouldn’t have been lined up in front of a firing squad to face the ultimate existential question. What happens now?

Dostoyevsky wasn’t shot. A minute before the firing squad was to pull the trigger, a horse rode into the jail yard and announced that the Czar had commuted the sentence. Instead of ending up with a bullet in the chest, Dostyevsky was sentenced to four years of hard labor in Siberia and then a few more in the Siberian regiment of the Russian army, something not considered a big improvement. Normally, you don’t get much of a hint as to what happens in the mind of someone staring at the business end of a bunch of emotional dullards pointing guns at you with less than 60 seconds to spare but, years later, he wrote a novel called the Idiot. In it, he describes a scene that fills in that blank for us.

“…But better if I tell you of another man I met last year…this man was led out along with others on to a scaffold and had his sentence of death by shooting read out to him, for political offenses…he was dying at 27, healthy and strong…he says that nothing was more terrible at that moment than the nagging thought: “What if I didn’t have to die!…I would turn every minute into an age, nothing would be wasted, every minute would be accounted for…”

Now, before one goes on to say that this is exactly the sort of thing you’d expect someone to think at a time like that, there is a difference between this and the modern, bucket-list approach to living each day to its fullest. Dostoyevsky wasn’t talking about visiting the pyramids and bungee jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. To him, the point isn’t that he could do more stuff if he lived. His point was that he would have to do more stuff if he lived. It wasn’t an option but an obligation. And the thing he would have to do was to made decisions. Decisions about things much more significant that, “where will I para-sail next?” And, with what he decided each time he asked the question, “What happens now?” he would add another brush stroke to the picture of who he was.

This is the heart of existentialism. Existence precedes essence. You are not born a person who then adds experiences to his or her personhood to become who you are today. You are not much of anything when you are born, at least not much of anything that can be called a person. All you’ve really got is your existence, and that’s not very much. And you don’t become the person you are based on the experiences you have. Everybody has experiences. Experiences are thing that happen to you. You become the person you are by the way you answer the very, very big questions that you don’t have the time or background to answer in the thoughtful, academic way that most of us like to answer big questions. Everyone knows that it’s better to be kind that to be mean. But when you least expect it, and the option to be kind seems so terribly remote, unnecessary, unnoticed and superfluous, the opportunity to do just that will present itself. Whether you are a kind or a mean person will be noticed as soon as the last decision-making neuron fires in your distracted head.