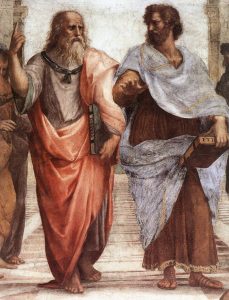

Plato was a realist, and that has caused us a lot of trouble. Plato believed that, if we were expected to give anything any real thought, it should actually exist. That things actually exist sounds self-evident. Rocks exist. Toads exist. People exist. But Plato also thought that things like beauty and courage exist. And we generally think that too. “What about someone who believes in beautiful things” he wrote, “but doesn’t believe in beauty itself? Don’t you think he is living in a dream?” In other words, to find something, or someone, beautiful, you have to believe there is such a thing as beauty, which is the thing that the beautiful thing or person possesses. And it’s the same for courageous people, intelligent people and good people. They possess courage, intelligence and goodness. Plato thought these things were as real as the people who possessed them. Aristotle made this much more complicated by adding categories in which things existed. He even wrote a book about categories called, to everyone’s surprise, “The Categories.” Everything that exists can be slotted according to an elaborate system of 10 categories. And he was full on board with Plato on realism.

But deep down, there is something sinister going on here because, if these things actually exist – courage, intelligence, goodness – then cowardice, stupidity and evil also exist. And, like courage, intelligence and goodness, people have these things too. Or, at the very least, cowardly, stupid or evil people don’t have the things that would make them courageous, intelligent and good.

Some people think that most of what’s wrong with this world comes from this way of looking at things. They’re called nominalists, and they have a different idea. Here’s the problem with realism, nominalists say:

Aristotle coined a phrase, one we translate “Universal”, to talk about these universal things like beauty and courage. The word he invented translates exactly as “on the whole.” Evil people are, on the whole, evil. They have a certain measure of evilness in them. We talk like this all the time. “You have your father’s Italian temper.” Temper exists in you like it existed in your father and exists in Italian people. And that begs the questions, what do Black people have? Or men? Or women? Or gay people?

Today, and at its most positive, this is called “identity.” But it’s dangerous stuff even when used positively. It could be that it’s most dangerous when it’s used positively. We talk about identity a lot more than we realize. Women are naturally nurturing. Men are naturally competitive. Gay people are born gay. Black people… (I’m not going there, but lots of people “identify as Black” in a lot of very specific ways.) Some like to think of these as stereotypes, but that word gets applied rather inconsistently by calling negative things “stereotypes” and positive things “identity”. That’s not very helpful and, if you are going to adopt Aristotle’s categories as we all do, it’s a distinction without a difference. What they really are, are attributes of the Forms that Plato and Aristotle gave us. Lots of times they are pretty harmless. Dwight Yoakam in a cowboy hat is sexier than Dwight Yoakam in a beret. And he’s sexier in a beret than I am, even in a cowboy hat. But here’s the problem. If sexiness exists as a real thing, not only is he sexier than me, but there are lots of other people who are sexier than me, too. They have something I don’t have. And that may well mean they are “better” in other ways too, and therefor more valuable. Why? Because they have membership in arbitrary categories making them worth more time, money, thought and affection. They are not only sexier than me, but superior to me in at least that category. And because we don’t know where to stop, superior to me in other categories, too.

Nominalists think there is a better way. Sexiness is not a thing sexy people have. And courage is not a thing that brave people have. They’re not things at all. Unlike realists, nominalists don’t believe these general categories are real. They’re a kind of symbol for a behavior, collection of behaviors, attributes, qualities, or what-have-you that seem to pop up in groups of people but are stuff that can only really be applied to individuals. Courageous people, and sexy people, certainly exist. I don’t doubt that Dwight Yoakam is sexier than I am. Lots of other people are, too. But that they have something special I don’t have isn’t true, according to nominalists. For example, imagine that there are a bunch of people on a battlefield, and that they all behave courageously. Imagine they are all men, a relatively common state of affairs on a battlefield. But, if you are a nominalist, you can never say “men are courageous.” What’s more, even if the sample is a billion men and 100% of them are courageous, you still can’t say it. You can’t even say “men are courageous” if it turns out that 100% of all men are, in fact, courageous. Because men are things and courage is a metaphor for a behavior. The best you can say is “there are 3.75 billion men in the world (including male children) and each individual one acts courageously.” If you think this way, racism disappears. You can’t say all indigenous people are lazy. You can’t even say that they tend to be lazy. And you can’t say it, not because it sounds terrible, which is does, or even because it’s not true, which it’s not. You can’t say it because it’s a stupid sentence. Laziness isn’t a thing, so no group can be said to possess it. Individuals can have behaviors that can be described as lazy, but being native can’t be the cause of it because laziness isn’t a thing any group of people can have. It’s not a thing at all, so no group can have it. If you are Aristotle, laziness is a category like being indigenous is a category. And it’s possible to mix and match categories to your racist heart’s content.

I can’t really say, “Aristotelian philosophers are dorks.” It seems true, but I can’t say it.