Wittgenstein tried to build a system in which everyone could communicate and in which no one could possibly be misunderstood. By his own admission, he didn’t do a very good job. At least not on the first go around. The idea is pretty much there, and he does improve on it a little later but, right out of the gate, it’s mindbendingly difficult to follow. He starts with the idea that the state of the world is made up of facts, not objects. This matters because objects are simple and most of us don’t see past the objects in the world. Because we only see the objects in the world, we think everything is simple and everyone else should be able to identify the things I am talking about as easily as I can. Even a dullard should be able to figure them out. That’s why, when someone says “pass the ketchup” one doesn’t expect the mustard. Mustard and ketchup, as objects, are easy enough to distinguish. But, says Wittgenstein, the world isn’t made up of objects like we have always believed. The world is made up of facts which are the state of affairs that happens when objects combine themselves in complex and (this is important) logical ways. A way is logical when the properties of the object combine with the properties of other objects to produce a state of affairs that is in keeping with the properties of that object. What’s important is not so much what ketchup “is” but that it arrive at your end of the table and ends up on your French-fries. The ketchup doesn’t matter. It’s the state of affairs that the ketchup participates in. When this happens, it becomes what they call an existent state of affairs and those existent states of affairs all combine to make up the world. Of course, you could still end up with mustard because mustard is an object that has enough properties in common with ketchup to still create a state of affairs that’s logical. This would be called a possible state of affairs. What isn’t possible or existent are states of affairs that are in inherently illogical combinations – for example, asking for the ketchup and getting world peace instead. That is not logical and so it is not possible. So we end up with three possible states of affairs. Ones that exist, one’s that are possible, and ones that are illogical which, really, are not states of affairs at all The world as we know it is made up of states of affairs that exist and only those that exist. No more and no less.

But how do you talk about these state of affairs? When you ask for the ketchup, what you are really doing is generating a thought that is a picture of the logical connections among the objects in the state of affairs, or what you hope the state of affairs to become – good friends having French-fries with ketchup for everyone. And for that to exist (and so become part of the real world), everyone involved has to have roughly the same picture in their heads. Language does this. If you can construct a sentence that can combine the objects (ketchup, friends, french-fries) logically then it is said to have meaning and you have a pretty good chance of getting ketchup on your fries. If your sentence includes elements that have no meaning then they cannot make up a legitimate thought. Those can’t be used to generate a useful picture and no one will know what the hell you are talking about. Asking for world peace when the objects available to you are ketchup, french-fries and friends is what Wittgenstein would call nonsense. Some sentences are obviously nonsense like “my cat is similar.” Others seem like they should make sense but don’t because the properties of the objects can’t go together logically to make a picture. “There are 12 inches in an hour.” And there are sentences that can create a picture easily enough but the picture isn’t the same from one person in the conversation to the next. “Last night was awesome.”

You can see where things could go wrong.

But Wittgenstein made some mistakes, some of which he was aware of and tried to straighten out pretty quickly. Others he noticed later and either tried to fix later in his life or simply tossed out the window depending on which interpretation of the rest of his wacky life you want to accept.

The first is that there seems to be some statements that are not nonsense but can’t really be talked about either, and if Wittgenstein was clear on anything it was this: If you can’t talk about it, you shouldn’t talk about it. If I say “my cat is similar,” it is clearly nonsense. If I say “our cats are similar,” it seems to make sense. But talking about it is futile because you can never generate a meaningful picture of “similarity” by talking about the objects. You need to show it. Wittgenstein accepted this exception.

But there are some things that are important, don’t seem to be nonsensical, still seem to be a part of the real world, but can’t be talked about according to Wittgenstein’s system. You can’t talk about love, for example. And sometimes you sort of have to. If you tell your significant other, “I love you,” you are already on thin ice because the picture in your head is very likely not the same as the the one in the head of your significant other. If you say “I love you as a friend,” you are in a Wittgenstein-ian world of hurt because no one understands what that means. Still, it seems like the sort of thing that should be talked about.

The other thing is that, using Wittgenstein’s understanding of language, you can only talk about things the properties of which are known (and agreed upon) enough to have thoughts. And these thoughts have to be meaningful enough to generate pictures everyone can agree on. According to Wittgenstein, you can’t say “I like unicorns” because that can never describe a state of affairs that exists (because there are no unicorns). They are not part of the world as Wittgenstein sees it because , if you remember, the world is only made up of states of affairs that exist. Even if you can get by with never talking about unicorns, you will have a bit of trouble if you were to substitute the word “God” for “unicorns.” Everyone can agree that unicorns don’t exist. Not so with God. And, really, talking about God is pretty inevitable. Even saying “I love you” is a problem because… well, you can work that one backwards on your own.

And one other problem: Wittgenstein says that our language defines the limits of our world. That’s a problem already for people who binge watch Netflix and have ended up with a limited grasp of language. But it’s also a logical problem. If you have a limit, it must imply the existence of something outside the limit. The speed limit is 70 mph because someone went to 71 and said, “Woah! That is way too fast.” The speed limit isn’t 70 because 71 doesn’t exist. So Wittgenstein’s insistence that nothing exists outside the limits of language is a contradiction if only because of the word “limit.”

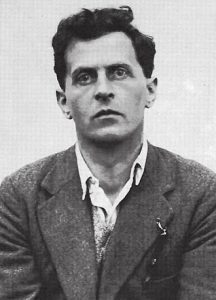

Wittgenstein published only one book in his life, a short piece of about 70 pages. The rest of his life he spent bouncing around working as a gardener, an architect, an officer on the front lines in WW1, an elementary school teacher (take a wild guess at how well that worked out), and a hospital porter in WW2. Somewhere in there, he seemed to have realized that he got something wrong and started writing another book in which he rethought the “picture” idea and instead started talking about language “games.” More on that soon.